Unelected globalists want to put a price on everything in nature, from the water we drink to the air we breathe: perspective

The unelected globalists at the World Economic Forum (WEF) say that natural systems are finite and should be put on a balance sheet because “we can’t do business on a dead planet.”

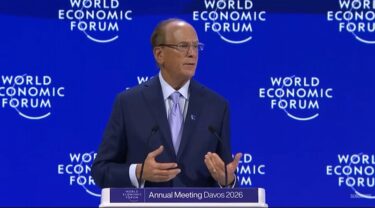

Speaking at the WEF Annual Meeting of the New Champions, aka “Summer Davos,” in Dalian, China on Wednesday, University of Cambridge Institute for Sustainability Leadership CEO Lindsay Hooper told the panel on “Understanding Nature’s Ledger” that every part of the economy depends on nature, and that in order to protect natural systems, one solution would be to “bring nature onto the balance sheet.”

“We can’t do business on a dead planet. If we’re going to protect natural systems, one of the solutions is to bring nature onto the balance sheet”

Lindsay Hooper, WEF Annual Meeting of the New Champions, 2024

“We can’t do business on a dead planet,” said Hooper.

“If we’re going to protect natural systems, one of the solutions is to bring nature onto the balance sheet; bring nature into the ways that decisions are made within business to allocate a value to it — to bring it into accounting and financial mechanisms,” she added.

Hooper’s reasoning comes from the belief that the ways in which we’ve grown our economies, which have allowed us to prosper, are “not sustainable on a finite planet.”

“The unintended consequences of current models of growth are simply not sustainable on a finite planet”

Lindsay Hooper, WEF Annual meeting of the new Champions, 2024

According to Hooper, “The ways in which we have grown our economies, our models of economic development, have been incredibly successful for global prosperity.

“The unintended consequences of current models of growth are simply not sustainable on a finite planet.”

Hooper’s words echo those of WEF founder Klaus Schwab, who at the opening plenary on Tuesday said that there were “limits to growth.”

“The theme of this annual meeting is ‘Next Frontiers For Growth,’ but actually what we have seen in the presentations there are now Limits to Growth, provided we use technologies of the fourth industrial revolution in a wise manner”

Klaus Schwab, WEF Annual Meeting of the New Champions, 2024

“Limits to growth” is a nod to the Club of Rome book of the same name published in 1972, and Schwab says that these limits can be overcome by using technologies of the fourth industrial revolution wisely, by taking care of nature, by seeing the green economy as a “great opportunity for humankind,” by exploiting the capabilities of the attendees, and by formulating collaborations between governments and businesses.

Getting back to the panel on “Understanding Nature’s Ledger,” Hooper suggested that nature should not be treated within the economy as though it were free and unlimited.

“Nature is treated within the economy as though it’s unlimited, and predominantly as though it’s free”

Lindsay Hooper, WEF Annual Meeting of the New Champions, 2024

“Without these forms of value, these forms of natural capital, we won’t have economies. They are the fundamental building blocks of our economies”

Lindsay Hooper, WEF Annual Meeting of the New Champions, 2024

“At the moment, the way that decisions are made on an every day level within businesses and financial institutions is because we’re looking at financial data metrics that are not factoring-in nature,” said Hooper.

“Nature is treated within the economy as though it’s unlimited, and predominantly as though it’s free.”

Why does Hooper believe that nature should be factored-in to financial data metrics?

According to her, it’s because “every part of the economy is fundamentally dependent on nature,” including, “the air that we breathe, the water we drink, the soil, the oceans that we need for the food that we need to consume, the minerals that we need as inputs to technology and into infrastructure.

“Without these forms of value, these forms of natural capital, we won’t have economies. They are the fundamental building blocks of our economies.”

In addition to putting “nature on the balance sheet,” another proposal coming at the end of the panel discussion suggested putting a tax on natural systems like water in the same vein as carbon taxes.

“Beyond carbon [taxes] let’s think about other aspects of nature that are easier to quantify […] What about water?”

Gim Huay Neo, WEF Annual Meeting of the New Champions, 2024

In her presentation, WEF managing director for nature and climate Gim Huay Neo said that “integrating natural capital to our accounting framework” should happen soon, stating:

“We need to keep pushing while continuing to refine and enhance, and the best example I can give is carbon pricing.

“Today, carbon pricing, ETS [Emissions Trading Systems], carbon taxes really cover about 25 percent of global emissions.

“We should actually look at scaling this to cover all 100 percent of carbon emissions.

“And beyond carbon let’s think about other aspects of nature that are easier to quantify.

“We will probably not be able to quantify everything on day one, but what about water?

“That’s quite possible for us to start integrating systematically into current trading carbon pricing mechanisms.”

The unelected globalists seek to put a price on everything in nature, from the water we drink to the air we breathe.

“We start thinking about putting prices on water, on trees, on biodiversity […] How do we start tokenizing? How do we start building systems that actually create not only the value, but transfer that value around the world?”

Ex-Bank of England Advisor Michael Sheren, COP27, 2022

At COP27 in November 2022, former Bank of England advisor and G20 co-chairman Michael Sheren said that carbon was “moving very quickly into a system where it’s going to be close to a currency,” and that next on the agenda was the tokenization of nature and biodiversity, where places like Indonesia, Brazil, and Africa would be “absolutely critical.”

“Carbon, we already figured out, and carbon is moving very quickly into a system where it’s going to be very close to a currency, basically being able to take a ton of absorbed or sequestered carbon and being able to create a forward-pricing curve, with financial service architecture, documentation,” said Sheren.

And with carbon being close to a currency, “There are going to be derivatives.”

Next on the agenda is the tokenization of water, trees, and just about everything else in nature.

“We start thinking about putting prices on water, on trees, on biodiversity, we find where does that sit?” Sheren pondered.

“How do we start tokenizing? How do we start building systems that actually create not only the value, but transfer that value around the world?”

“When we speak about Mother Earth and our ecosystem, when larger companies speak about its value, for us this ecosystem is a sacred ecosystem; there’s no value to it; it’s invaluable”

Uyunkar Domingo Peas Nampichkai, WEF Annual Meeting in Davos, 2024

Fast forwarding to this year’s WEF Annual Meeting in Davos in January, they held a similar panel called, “Putting a Price on Nature,” where Amazonian community leader Uyunkar Domingo Peas Nampichkai said that it was impossible to put a price on a sacred, living ecosystem.

“When we speak about Mother Earth and our ecosystem, when larger companies speak about its value, for us this ecosystem is a sacred ecosystem; there’s no value to it; it’s invaluable,” he said.

According to Peas, putting a value on nature would be like trying to put a price on your mother.

Image Source: Screenshot of Lindsay Hooper from WEF Annual Meeting of the New Champions panel on “Understanding Nature’s Ledger.”