If we want robots to do things that we as humans can’t, then shouldn’t robots look and function differently from us?

Recently, Google introduced its home-assistant robot’s capability to book an appointment. The conversation involved very human awkward pauses and deliberation. It was designed for us not to detect the machine in it. Fascinating as that is, for many, there is an undeniable sense of foreboding as well.

Robotics experts, such as University of Edinburgh’s Robert Fisher, is not in favor of the concept of human-like robots. “I don’t think artificial intelligence will ever be like humans,” he told The Guardian.

“We put ourselves and them in a difficult situation by trying to pretend they are human, or make them look like us. Maybe it is better not to do that in the first place. Sex robots is perhaps the only case where there is a reason for them to look human.”

Read More: World’s 1st conference on ethics of sex robots launches in UK

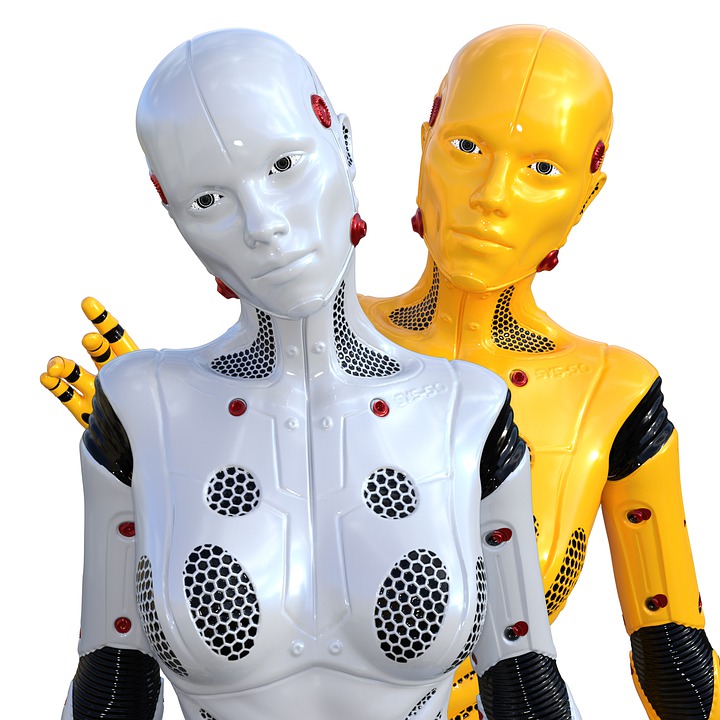

In science fiction shows and movies, while there are some humanoid robots that we find endearing, such as Data in Star Trek, there are others that make us cringe, such as Ava in Ex Machina and Niska or Mia in Humans.

In contrast, non-human robots such as Wall-E, R2D2 in Star Wars, Weebo in Flubber, and Marvin in Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy, are all endearing. It will take time for users to get used to the idea of interacting with humanoid robots.

Anouk van Maris, a robot cognition specialist studying ethical human-robot interaction finds that the people’s level of comfort with robotic interaction differs from location to location on the basis of culture.

“It depends on what you expect from it. Some people love it, others want to run away as soon as it starts moving,” she told The Guardian.

“The advantage of a robot that looks human-like is that people feel more comfortable with it being close to them, and it is easier to communicate with it. The big disadvantage is that you expect it to be able to do human things and it often can’t.”

While the Japanese are already comfortable using robots as shop assistants, in care homes, and in schools, Europe and the US are designing home-assistant robots in the form of black boxes with mechanical voices.

Read More: Tackling senior isolation and loneliness with technology and travel

Japan faces the problems of an ageing society, which gives rise to the demand for nursing staff and caregivers. Hiroko Kamide, a Japanese psychologist who specializes in human-robot relations, says that in ageing societies, “robots will coexist with humans sooner or later“.

Japan’s humanoid robot Erica and Gatebox AI’s Azuma, which is the Japanese equivalent of the Amazon Echo, are some of the most creepily human-like robots.

In 2017, social humanoid robot Sophia was given Saudi Arabian citizenship. The robot, which (who?) was developed in the female form by Hong Kong based company, Hanson Robotics. Sophia is the first robot to gain legal personhood and is now pursuing a career in marketing.

Read More: Walk This Way: Sophia the Robot Tests Her New Legs

It goes to say that a robot is liable for legal personhood, when it resembles humans. We wouldn’t then bestow legal personhood on a computer programme because of its lack of limbs. As humans, we are prone to develop an emotional attachment with objects that resemble humans.

Even as children, we attribute human feelings and traits to dolls and action figures, which is why we are sad when they break. Could our attachment grow to the extent that we start fighting for their rights?

Read More: Artificial vs Emotional Intelligence in Machine Learning

As soon as a machine starts mimicking a human, we are bound to face attachment issues. Imagine your smartphone as a human robot. Wouldn’t it be difficult to exchange it every year for a better model?

As humans, we are bipedal, can’t fly, don’t have chameleon vision, and have only two limbs to work with. If robots are being created to do more or better work than us, shouldn’t they not have our weaknesses?