There is hardly anything in modern life that someone, somewhere, hasn’t already created an app for. If there’s a phrase that best defines the past decade, it’s probably, “we’ve got an app for that”.

So, when the world is overtaken by a massive, global public health crisis, it’s not surprising that the first thing many smart people thought was, “how can we use smartphones to fix this”.

It is not an entirely unreasonable idea. Apple and Google are two of the largest companies on earth, with massive financial and technological resources, and deep consumer penetration. Eighty percent of Americans own either an Apple or Android smartphone.

The majority of the public gets their daily news from portable devices. There is no medium in human history that has ever provided a better opportunity for rapid dissemination of information to either the general public, or carefully targeted groups of individuals. What’s not to love?

But as they say: the devil is in the details.

Public health maintenance presents a unique range of complexities that makes it particularly unsuited for the sort of one-size-fits-all approaches that tech firms are most effective at designing.

And contact tracing — the specific public-health tactic currently being addressed in a joint proposal by Apple and Google — has its own specific requirements and limitations that reduces potential benefits that mobile technology solutions can provide.

Contact tracing ‘some, but not all’ won’t help

Contact tracing, to be effective, requires interviewing people who have tested positive for infection, and determining who they have had intimate contact with so that those people can themselves be contacted and screened. By focusing on highest-risk people, rapid spread of contagion can be contained.

But the automated smart-phone tracking systems proposed are by their definition ‘non-comprehensive’. They omit anyone who doesn’t own and carry a smartphone on their person 24/7.

Additionally, a large percentage of people say they simply would not participate in any such system.

While mobile technology provides unique capabilities, they simply don’t add value if they are neither comprehensive nor universally adopted.

Tracing… without identity?

There is also the problem of “who”.

Mobile-phone based contact tracing proposes to function without exposing identities of end users. This is a sensible precaution given the nature of the technology, which exposes the behaviors/interactions of millions of people to direct surveillance.

But the reality is that individual identity is crucial to effective tracing. Without it, the public health mandate is made toothless.

The traditional approach to tracing is for infected persons to provide public health authorities with personal information about who to contact.

Distinguishing who is worth following up with, and who is not, is a crucial qualitative step that helps ration public health resources. The approach that the automated technology takes has no mediating, qualitative ability to distinguish significant contacts from inadvertent ones.

People standing on opposite sides of a wall may be treated the same as those in bed together. This results in an explosion of false-positives, ultimately requiring human intervention to sort bad-data from useful-data, and undermining effective resource rationing.

Who is ultimately responsible?

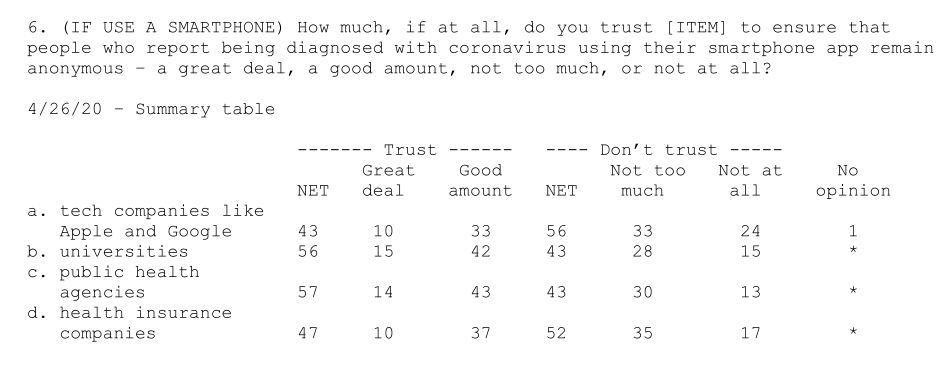

Probably among the less-discussed aspects of the contact-tracing proposals, but one best illustrated by lukewarm public support, is the matter of ‘Who will be responsible for protecting the data’.

Public support for sharing of personal health information plummets when it involves big tech companies rather than public health agencies.

This creates a Catch-22 for smartphone companies: the only way you can get a majority to use a contact-tracing application is to assure them that they are not themselves directly involved in handling personal health information.

And while Apple and Google have promised to provide security to all data in transit, such that no loss or theft would expose an individual’s information, the same assurances can’t be made for those who will be responsible for developing applications to analyze said data, and ultimately use it in policy-making.

Image source Washington Post: University of Maryland national poll, April 21-26, 2020

Why government developers are the weak link

The proposed system by itself has fairly robust data protection built into its protocols. But the end-users of the data being collected – government and public health agencies – will be the ones responsible for developing applications that utilize and analyze the underlying data.

This fragmentation of responsibility allows the smartphone companies to wash their hands of responsibility in the event of any data-loss or security breaches. And data breaches – particularly in the public health arena – are increasingly common.

Medical practitioners tend to be particularly strict about handling patient data because of Federal regulations like HIPAA, which specifically bars exchanging personal health data between agencies.

The technology provided by Apple and Google creates an apparent exception to this policy, and a vast opportunity for risk.

Better late than never? Or not…

The most important time to utilize contact tracing is in the earliest stages of an outbreak, to contain it before it spreads to the wider population.

While unstated in the current Apple/Google proposals, the practical utility of the technology will be for future use rather than the current problem, to deal with recurring rounds of COVID exposure, or potential new virus outbreaks.

And it is certainly possible that mobile-phone apps will prove to be very useful in helping deal with subsequent outbreaks.

But the current proposed technology, designed for large scale population-surveillance, may not be especially useful in the context of small, localized outbreaks, where contact-tracing is most effective.

The irony is that technology provides its greatest benefits at large scale: but by the time an outbreak has spread to a significant share of the population, containment via contact-tracing is no longer a particularly helpful method.

The bottom line

Overall, there’s reason to remain optimistic about the potential of mobile-phone technology to play a vital role in future public health crises.

However, for anything to be truly effective, it will require:

- Universal, voluntary adoption by the public.

- Clear disclosure and transparency about how data will be collected and used, and what agencies will be responsible

- Federal laws like HIPAA will need to be updated to reflect changes in how people’s personal health information is shared between public and private entities.

These won’t happen overnight. However, these developments are likely inevitable, and should be prepared for.