In his book, Poverty, by America, sociologist Matthew Desmond explains the significance of poverty in the United States.

“If America’s poor founded a country, that country would have a bigger population than Australia or Venezuela. Almost one in nine Americans — including one in eight children — live in poverty. There are more than 38 million people living in the United States who cannot afford basic necessities, and more than 108 million getting by on $55,000 a year or less, many stuck in that space between poverty and security.”

What’s interesting about poverty in the US is that it is not a new problem. It’s also not an underfunded problem — in fact, there are $665 billion (or 11 percent of the federal budget in 2022) dollars a year earmarked for programs designed to fight poverty.

Nevertheless, Desmond compares the battle against poverty in America to rolling hills. That is, it never really peaks or finds resolution. It also never really bottoms out to the point of becoming a dominant focal point.

Despite efforts on all levels of government, poverty — in one of the wealthiest nations on the planet — persists.

Why?

Poverty is a complex issue, what Desmond calls a “tight knot of social maladies.” So pointing to one cause or looking for one silver bullet solution is a mistake.

But something that does seem fixable, or at least made more efficient through technology, is the major waste that results from the way that financial assistance is delivered. There are new web3 technologies that can help address those inefficiencies by means that are transparent, fair, and scalable.

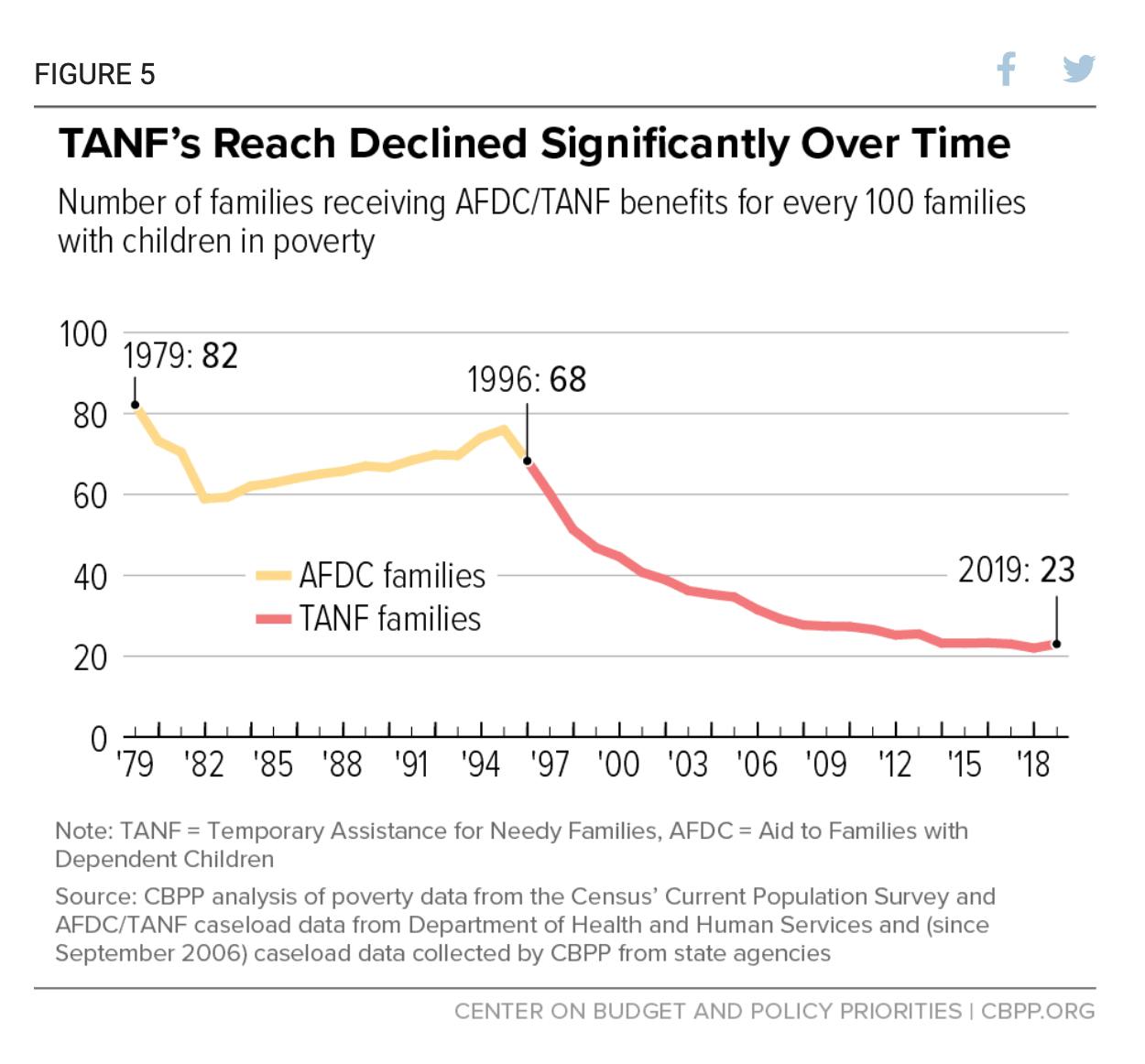

Currently, money moves through multiple layers before arriving at the people that actually need help. In some instances, because all the layers involved act like the monetary version of a prism refracting light instead of focusing it, the money earmarked for poverty alleviation never actually reaches its target. According to estimates by Desmond, only 22 cents for every dollar of money spent on the federal Temporary Assistance for Needy Families (TANF) social assistance actually gets to the people that need it.

Or if it does, it’s not really in the form that is the most beneficial, which is often just a cash payment.

One of the biggest reasons that TANF funds aren’t making more of an impact is that they are first given to state governments in the form of grants. Individual states can choose how the money is used. Some states don’t spend the money at all, while others spend it on projects not directly related to helping families in poverty.

According to an analysis of 2021 data by the Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, “States only spend a little over one-fifth of their combined federal and state Temporary Assistance for Needy Families (TANF) dollars on basic assistance for families with children…States continue to use their considerable flexibility under TANF to divert funds away from income support for families and toward other, often unrelated state budget areas. By redirecting the funds back toward cash assistance, however, states could do more to strengthen economic security and promote racial equity and child well-being.”

In other words, alleviating poverty isn’t as much of a funding issue as it is a delivery issue.

Assistance to people that need it the most has a last-mile problem that exists with other forms of public infrastructure too. Giant pipelines of financial assistance exist, but they often don’t connect with people in a way that is meaningful or immediately impactful.

This is where the idea of universal basic income comes in.

Universal basic income and web3’s open distributed ledger

The driving concept behind universal basic income (UBI) is a regular, recurring income that is not tied to a job or any other kind of government program. Instead, money is given to wide swaths of the population to make financial assistance more equitable and accessible.

UBI gives its recipients the option to buy food or upgrade housing or deal with healthcare costs — or whatever. The point of UBI is to make sure that everyone is able to get their basic needs met.

Proponents of UBI point to the idea that a simple cash payment allows each person to decide how and where to best use the money. The ownership and agency implied in the UBI model are way different than the government funds arriving as part of predetermined programs.

It also acknowledges that access to services is becoming more privatized (requiring money for entry) and that needs are dynamic. For people that already have enough to eat, a safe place to live, and access to healthcare, UBI provides a chance to increase health and security on other fronts — and better prepare for the future.

On a macro level, UBI is a proactive social welfare net that could result in lower public safety, healthcare, and education costs. The feeling of security and prosperity might also have follow-on effects like increased social stability.

A recent report from the Tony Blair Institute for Global Change about using web3 to efficiently and fairly deliver UBI like this: “Increasing within-country inequality not only hurts the aggregate demand and, therefore, the growth potential of an economy, it also reduces the prosperity of the average citizen and becomes a significant driver of social instability.

Data from the 2020 Global Peace Index show that civil unrest has increased over the past decade around the world. Between 2011 and 2018, the number of protests and riots roughly doubled, while the number of general strikes quadrupled. There may be a direct link between growing economic inequality and the decline of social cohesion within a country.”

But UBI is not without its costs. And it’s when talking about funding that most conversations start to get tangled.

Would UBI increase taxes? Does it fit into free market capitalism? Is it even fair?

These are all valid points and questions. But the point here is not to dive into the politics around UBI, but instead, articulate that there are new kinds of innovations that can address one of the main challenges to UBI — and to public assistance in general.

Regardless of how UBI is funded — it could be a redirection of social welfare programs that already exist, funded by some other means (some places, like Alaska, have a form of UBI funded by fees paid because of natural resource extraction), or maybe even a new kind of staked digital asset network — the point is that web3 tools are a good fit to reduce the cost and management issues traditionally associated with distributing financial assistance at scale.

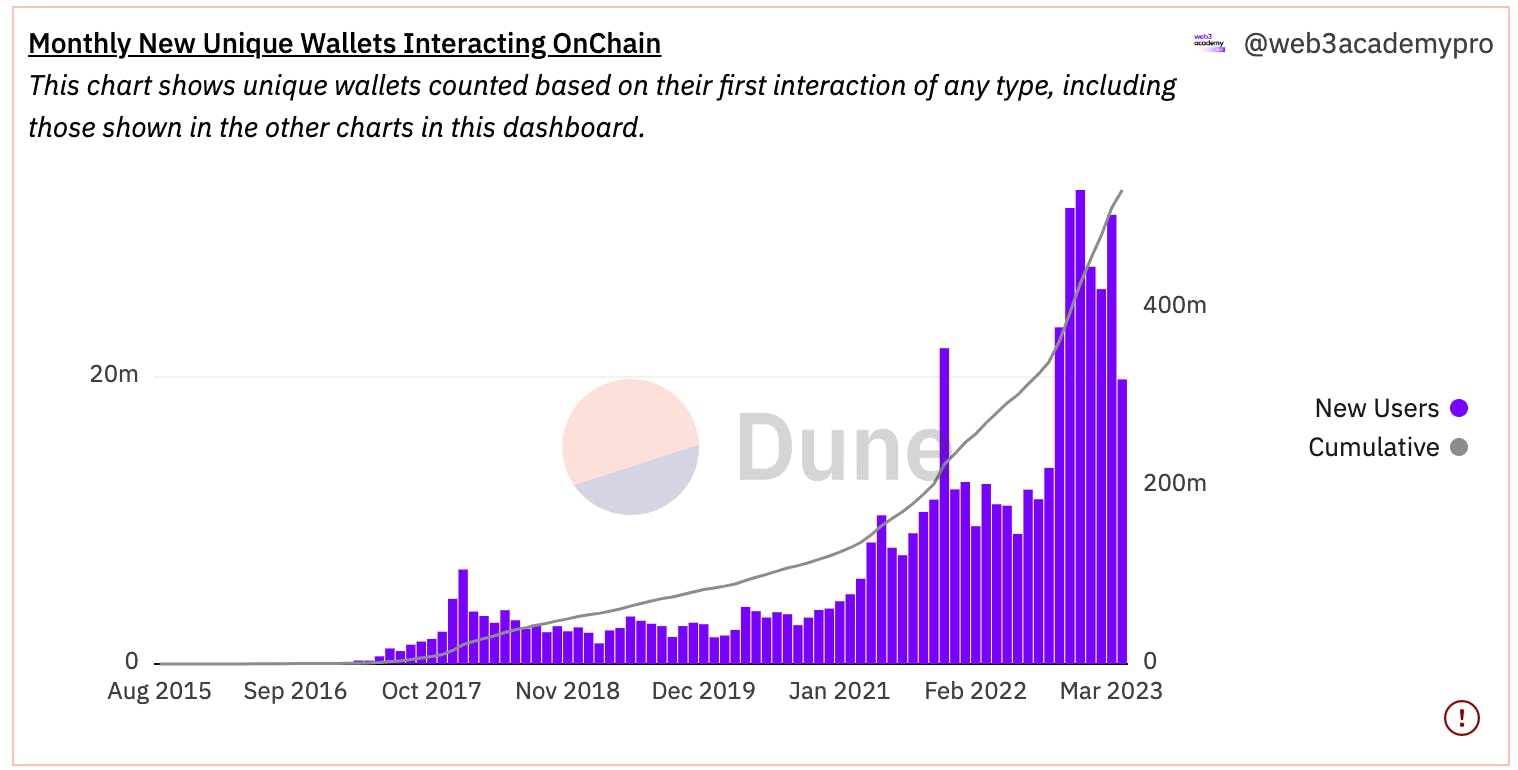

Data showing the growth of web3 users. Source

Open money and on-chain innovation

By the nature of being universal, a new system of on-chain basic income would also drive adoption rates of digital assets. And there is a massive opportunity to remake financial systems during the shift to a personal digital asset wallet system.

The combination of a verifiable digital identity, the ability for people to easily create and maintain a secure (including backup ability) digital wallet that is device and platform agnostic, could be a massive step forward for the delivery of on-time and truly useful social services.

One of the greatest attributes of combining on-chain infrastructure, Web3 tools, and social assistance is that the delivery of funds can happen wherever and whenever, regardless of physical location, employment status, or bank account activity.

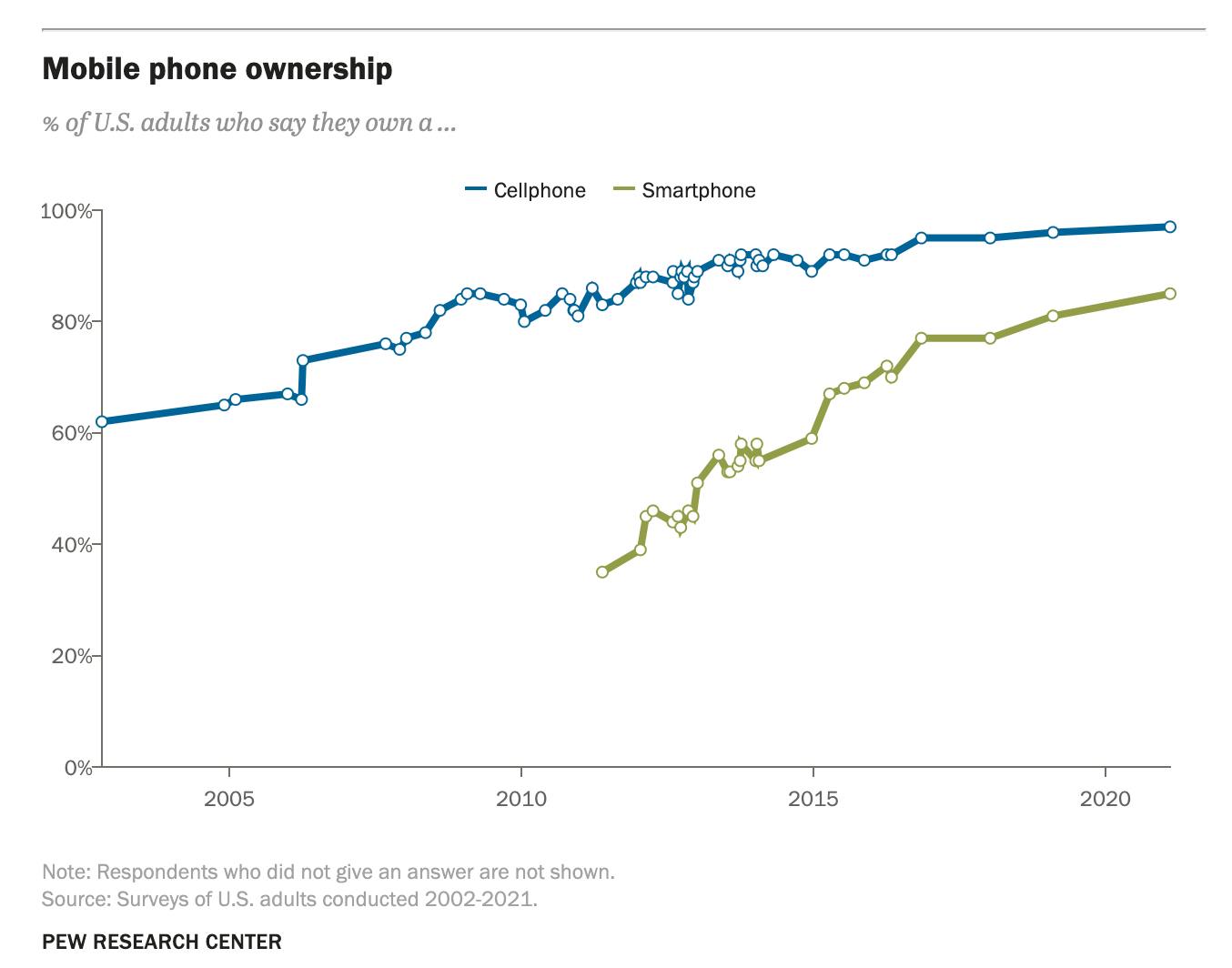

By using Web3 tools, all the recipient would need is a digital wallet on a mobile phone, and the rate of mobile phone ownership among adults in the US is nearly ubiquitous.

Besides solving the delivery issues of social assistance, switching to an on-chain system would also increase equity and accessibility across other parts of the financial system.

The current banking system is designed for people with money and is generally costly and cumbersome for people that are just making ends meet.

Circling back to Desmond’s book, he mentions the bank overdraft fees as just one example, “The deregulation of the banking system in the 1980s heightened competition between banks. Many responded by raising fees and requiring that customers carry minimum balances. In 1977, over a third of banks offered accounts with no service charge.

By the early 1990s, only 5 percent did. Big banks grew bigger as community banks shuttered, and in 2019, the largest banks in America charged customers $11.68 billion in overdraft fees. Just 9 percent of account holders pay 84 percent of these types of fees. Who were the unlucky 9 percent? Customers who carried an average balance of less than $350. The poor were made to pay for their poverty.”

Not to mention the entire system of check cashing and payday loans that charge insane amounts of short-term interest just to access some basic cash flow financial services. Again from Poverty, By America: “In 2020, Americans spent $1.6 billion just to cash checks. If the poor had a costless way to access their own money, over a billion dollars would have remained in their pockets during the pandemic-induced recession.”

The list of examples of how costly it is to be poor in the United States goes on and on, but the takeaway is clear: There has got to be a better way to create financial alternatives for the people that need them most.

And now, because of distributed digital ledgers, there is.

By building on open blockchains, UBI could be made to be transparent and auditable. This would allow watchdog and reporting groups to make sure the government and/or the public agencies responsible for administering UBI or other basic financial services were fulfilling their obligations without waste or fraud. This layer of transparency at the top would increase the overall faith and “buy-in” to the overall system.

At the level of individual people using web3 tools like non-custodial digital wallets, identity verification and protection, and the ability to move assets to multiple places including easy send and receive functions, provides a level of ownership and control (or personal sovereignty) that is not possible within the context of current financial systems.

This article was originally published by Daniel McGlynn on Hackernoon.