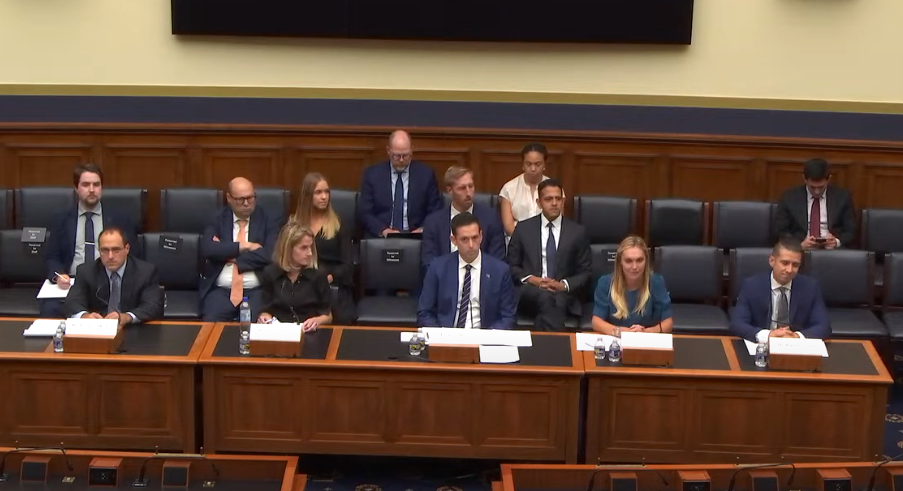

Expert witnesses on Central Bank Digital Currencies (CBDC) and fintech tell American lawmakers that programmable CBDC may lead to serious abuses of power and that there is little evidence that a CBDC would strengthen the economy or help bolster financial inclusion.

The House Financial Services Committee Subcommittee on Digital Assets, Financial Technology and Inclusion held a hearing on Thursday entitled, “Digital Dollar Dilemma: The Implications of a Central Bank Digital Currency and Private Sector Alternatives,” with five expert witnesses:

- Dr. Norbert Michel: Vice President and Director, Center for Monetary and Financial Alternatives, Cato Institute

- Christina Parajon Skinner: Assistant Professor, The Wharton School of the University of Pennsylvania

- Raúl Carrillo: Academic Fellow, Lecturer in Law, Columbia Law School

- Paige Paridon: Senior Vice President and Senior Associate General Counsel, Bank Policy Institute

- Yuval Rooz: Co-Founder and Chief Executive Officer, Digital Asset

In his written testimony, Dr. Michel warned:

“The possibilities for the programmability of a CBDC are nearly endless. And in all of them, even the best of intentions are just a few steps away from leading to serious abuses of power”

DR. NORBERT MICHEL, WRITTEN TESTIMONY, HOUSE FINANCIAL SERVICES COMMITTEE 2023

When asked, “Why would the federal government want to control what its citizens spend money on?” Dr. Michel responded:

“Politically, it [CBDC] is a nightmare for either side. It could be used to stop labor unions; it could be used to stop people spending things on gas stoves; it could be used under any political guise as desired.”

Dr. Michel added that there had already been government crackdowns on speech and protests in other countries without the help of CBDC, but that CBDC “exacerbates all these political problems; that’s exactly what this does, and that’s exactly why we shouldn’t have one.”

“The government provider of a CBDC could easily put money directly into a citizen’s account and, just as easily, take money out”

DR. NORBERT MICHEL, WRITTEN TESTIMONY, HOUSE FINANCIAL SERVICES COMMITTEE 2023

“The programming capabilities of a CBDC could mean that people would be prohibited from buying certain goods or limited in how much they might purchase”

Dr. Norbert Michel, Written Testimony, House Financial Services Committee 2023

In his written testimony, Dr. Michel added:

“The programming capabilities of a CBDC could mean that people would be prohibited from buying certain goods or limited in how much they might purchase. For example, advocates have quipped that parents could program their children’s lunch money with the condition that it can’t be spent on sweets.

“It’s important to consider the extended possibilities of such an option because the technology enables that type of programmability.

“Like parents trying to control their children, policymakers could try to curb drinking by limiting nightly alcohol purchases or prohibiting purchases for people with alcohol-related offenses.”

“In the case of the government-mandated lockdowns during the COVID-19 pandemic, a CBDC could have been programmed to only exchange with ‘essential’ businesses or alert the authorities when citizens incurred travel expenses”

DR. NORBERT MICHEL, WRITTEN TESTIMONY, HOUSE FINANCIAL SERVICES COMMITTEE 2023

In her opening statement, Christina Parajon Skinner told Congress, “There is no discernable reason for the United States to move toward a CBDC right now,” and that central banks were motivated by the underlying assumption that CBDC would replace cash in the long run.

“Because central banks don’t have the technology presently to offer cash-like privacy, a digital currency, unless it’s radically re-designed, will bring with it the ability for the state to monitor or surveil its citizens’ payments activities”

Christina Parajon Skinner, Testimony, House Financial Services Committee 2023

“CBDC as programmable money is a far cry from an inalienable property right of the natural law tradition adopted by the Framers and intended in the Constitution.

Christina Parajon Skinner, WRITTEN TESTIMONY, HOUSE FINANCIAL SERVICES COMMITTEE 2023

It leaves permanently open the question of whether and when the value stored in an individual’s CBDC could be digitally adjusted to meet the State’s objectives”

In her written testimony, Skinner argued that CBDC was more like a policy instrument rather than a property right.

“CBDC is a programmable form of money. Accordingly, CBDC is more a policy instrument than a property right, which makes it highly distinct from cash,” she wrote, adding, “It can be programmed to, for example, offer remuneration or not (and to adjust that rate or apply it to individuals or groups selectively).

“This feature alone makes CBDC a ready-made tool for new sorts of monetary policy interventions, including, perhaps most notably, the ability to defeat the so-called effective lower bound (‘ELB’) by imposing negative interest rates.

“The ability to manipulate remuneration rates on CBDC would also enable the Fed to implement new kinds of quasi-fiscal stimulus or conduct outright fiscal transfers (e.g., by ramping up the remuneration for some groups or purchases but not others).”`

“On balance, we believe that — at this point — there is little evidence that a CBDC would bring measurable benefits to the US economy, or that it is necessary to defend the dollar’s status as the world’s reserve currency”

Paige Paridon, Written Testimony, HOUSE FINANCIAL SERVICES COMMITTEE 2023

Representing the Bank Policy Institute — an advocacy group representing the nation’s leading banks — Paige Paridon said that there was “little evidence that a CBDC would bring measurable benefits to the US economy,” and that “a CBDC would be unlikely to meaningfully increase financial inclusion.”

In her written testimony, Paridon asserted that “By attracting deposits away from banks, particularly during a period of economic stress, a CBDC would likely undermine the commercial banking system in the United States, and severely constrict the availability of credit to the economy in a highly procyclical way.”

While groups like the International Monetary Fund (IMF) say that a CBDC would increase financial inclusion, Paridon argued:

“An intermediated CBDC is unlikely to address one of the primary reasons why certain individuals remain unbanked: because they lack the financial resources to open and maintain a bank account”

PAIGE PARIDON, WRITTEN TESTIMONY, HOUSE FINANCIAL SERVICES COMMITTEE 2023

“In the intermediated model,” Paridon added, “there likely would be fees associated with maintaining a digital wallet with the intermediary and for the related services provided by that entity.

“In fact, we are unaware of any substantiated use case for CBDC that would benefit low- and moderate-income people.

“So far, assertions about a CBDC increasing financial inclusion seem to be more rhetoric than reality.”

“When we narrow the digital dollar to CBDC and the conversation to the Fed, we do a disservice to the public […] At a minimum our conversation should include a discussion of the Treasury and its many bureaus, including the Mint, Bureau of Engraving & Printing, Bureau of Fiscal Service, and the Secret Service who are involved in the deployment of financial technology every day”

Raul Carrillo, Testimony, HOUSE FINANCIAL SERVICES COMMITTEE 2023

In his opening statement, Raul Carrillo argued that a digital dollar didn’t have to be a CBDC run by the Federal Reserve, but that other bureaus of the Treasury could take on this responsibility.

The same idea was put forth two years ago by expert witness Rohan Grey, when he testified in June 2021 that:

“Contrary to popular misconception, the Federal Reserve is not, and has never been, the only entity responsible for issuing currency or providing public payment services.

“Throughout American history, the [US] Mint, the Bureau of Engraving and Printing, the Bureau of the Fiscal Service, and the US Postal Service have all designed, issued, and operated various forms of public monetary technologies.

“It is thus a mistake to equate and reduce the wide spectrum of digital fiat currency architectures and arrangements to the more limited category of Central Bank Digital Currency, which refers only to those models in which central banks are the exclusive issuers and administrators,” he added.

“The major financial surveillance threat in the US is not in the public or private sector per se, but in both, and more importantly in the links between them”

Raul Carrillo, Testimony, HOUSE FINANCIAL SERVICES COMMITTEE 2023

In his written testimony, Carrillo elaborated on his privacy recommendations for policymakers:

“Ultimately, the only surefire way to protect privacy is for policymakers to provide devices that enable offline transactions. Government-issued bearer money like paper cash and metal coins can enable payments beyond the sight of powerful institutions. Digital bearer money can achieve the same goal.

“For example, stored-value cards (a type of “smartcard”) store money on the cards themselves, facilitating transactions that do not generate data for online systems to collect, store, share, or score.

“We already use relevant technology that functions offline, connecting devices to each other rather than a network.

“Devices using Bluetooth, near-field communication (NFC), or QR codes could enable payments while avoiding internet surveillance. Subject to network design, phone-based SIM cards can accomplish the same function.”

“Without a proper policy framework and absent a strong partnership between the public and private sectors, private sector initiatives may displace activities properly considered public goods—specifically money—that are due the protections offered by our Constitution”

Yuval Rooz, Written Testimony, HOUSE FINANCIAL SERVICES COMMITTEE 2023

Yuval Rooz, in his written testimony, argued that public-private partnerships should be leveraged in the case of a digital dollar, and that “leveraging blockchain technology to modernize financial infrastructure is critical to ensuring our continued global financial competitiveness and the dollar’s status as the world’s reserve currency.”

“As we’ve seen with the invention of the Internet, without a proper policy framework and absent a strong partnership between the public and private sectors, private sector initiatives may displace activities properly considered public goods—specifically money—that are due the protections offered by our Constitution,” he wrote.

For that, Rooz made two requests:

“First, that Congress ensures that any digitally-represented dollar, whether a stablecoin or a central bank digital currency, lives within our Constitutional framework—Americans using this digitally-represented dollar should have the assurance that their privacy rights are protected under our Fourth Amendment framework.

“And second, that Congress works closely with the private sector, and leverages technologies already built and proven, to serve as the rails for any digitally-represented dollar.”