With the privilege of being part of an organized profession, there are some annoying duties as well. For instance, as a new associate of the Order of Engineers, I was strongly invited to participate in a semi-mandatory six-hour seminary about ethics in the engineering realm.

The mere prospect of enduring an endless sequence of slides about vapid theoretical moral principles was, frankly speaking, bewildering: do we seriously think we can lecture adults about ethics?

However, as I am a quite rational individual (most of the time), I convinced myself that maybe it wouldn’t be that bad, that I was being too close-minded about it, and that I could learn a thing or two from the experience. Maybe, I dared to think, it’ll even be fun.

As expected, the presentation was an endless sequence of slides about vapid, theoretical moral principles, with minimal interaction from the participants.

All in all, it started off as an unremarkable experience that I would totally forget in a few days. Unfortunately, there was way more to it.

The Trolley Problem

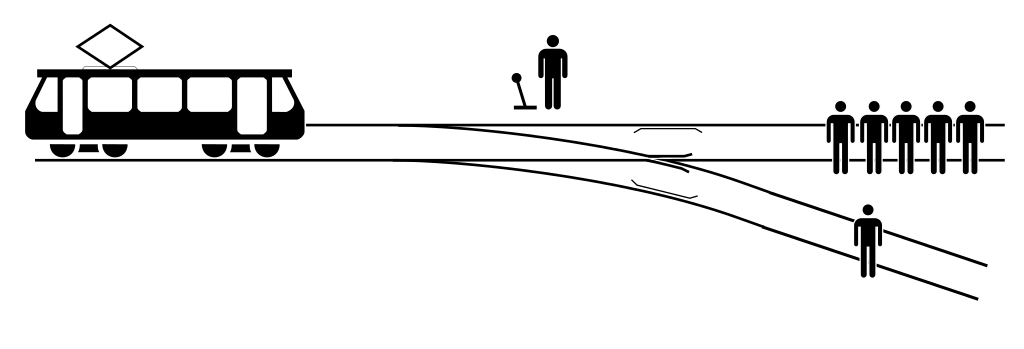

The trolley problem is a famous mind experiment that is often used to discuss ethical issues. In this experiment, we are asked to put ourselves in the shoes of a bystander witnessing an out-of-control tram rattling at full speed.

Let’s imagine that, further along the railway, there are five people tied to the rails and unable to escape like in a cartoon from the 50s: if you do nothing, you will spectate a very gruesome incident. That’s not all: in fact, you are facing a dilemma.

Next to you, there is a lever that can switch the tracks and divert the train, saving those helpless people. However, in doing so you would kill another defenseless person, that some villain tidied to the rails in the alternative route.

What do you choose: to do nothing and let five people die or to kill one person to save all the others?

An illustration of the trolley problem. By McGeddon / CC BY-SA 4.0

This problem was not designed to have a correct solution, but rather as a tool to meditate around the ramifications of decisions that bear serious consequences.

Imagine my shock when I figured out that the lecturer was expecting a serious response from us and, on top of that, he would even evaluate our moral compass according to our decision.

“Ah!” the lecturer commented with a sarcastic smirk on his face. “So this is your choice? I sincerely hope you aren’t involved in any serious decision at work.”

I felt so insulted, and I was on the verge of rage-quitting the presentation. However, I calmed down a bit when he explained what the superior moral choice was, according to him.

One should never intervene in a way that causes any side-effect, even if doing nothing will harm more people: nobody shall have the authority to take this kind of responsibility, no matter the cost.

At that moment, a devilish grin appeared on my face, as I realized I had a better route of action rather than administering free insults: I had the opportunity to corner the imposter and unmask him in front of everyone.

Law and Justice

The lecturing bully continued his rant by venturing into the debate about law and justice. Is lawful the same as ethical and just? According to the lecturer, yes. Respecting the law is the only appropriate ethical route.

Again, I admit that I was a bit surprised. Surely, respecting the law is usually the correct thing to do, even if it’s inconvenient and painful. Dura lex sed lex. However, there can be some cases where the law isn’t necessarily just, and many instances where unethical behavior is perfectly legal.

“Defying the law is always morally unacceptable.” the lecturer stated. “Unless doing so doesn’t harm anybody, if you immediately denounce yourself, and if you are ready to face all the consequences of your disobedience.”

“What if,” I interrupted him, “What if we lived in a liberticidal regime, and the law required us to harm our neighbor because he belongs to an unwelcome minority? Surely it can’t be unethical to break a law like that by standing back.’“

“No,” he replied angrily. “You have to always follow the law! Do you want to be like one of those rowdy No-Vax refusing to be vaccinated because they claim to be in a dictatorship?”

Now, there is so much to unpack here, and I don’t want to go too deep into this slippery slope.

Also, I am not sure to which laws he was referring, and honestly, at that point, I didn’t give a flying duck about his nonsense. The interesting thing is that he was overtly being in contradiction with himself.

“But earlier,” I retorted, “You claimed that it is unethical to take a decision that harms the individual to save more lives. Isn’t a vaccination campaign a textbook example of the trolley problem, where one protects the community at the expense of individuals suffering from fatal side effects?”

The lecturer’s face turned red – for the anger or the embarrassment, I am not sure – blabbering that the two situations were totally different, that my comment was off-topic, and that we still needed to cover many slides before the end of the lesson. I felt victorious.

Morality Shmorality

Something that really grinds my gears is that, for some reason, software engineers and other IT professionals are often singled out when it comes to “teaching” ethics.

It’s like someone feels we need to be “educated” because now technology is too powerful to be left in hands of some random nerd.

What about the moral compass of all the other professions? Do accountants, marketing experts, and strategy consultants need any refresher on ethics? What about taxi drivers, dustmen, or bakers? All of these jobs are a relevant part of society.

Instead, ethics in the third millennium is all about self-driving cars, AIs, or – more rarely – social media manipulation, as if all engineers were conspiring to bring forth a technological dystopia.

If anything, politicians and executives have vastly greater influence and insider knowledge regarding the functioning of our society. What is their answer to the trolley problem?

Conclusion

My fundamental issue with teaching ethics is that you can’t teach it as you would with geography or math. It is absurd to give precepts like “don’t lie”, “don’t steal”, and “be diligent” past the middle school stage and expect them to be of any use.

Adults are already familiar with the gist: the problem is applying ethics to real-life scenarios. I’d happily join a discussion when good-faith arguments are presented and I can improve my perception of the world and the nuances of human interaction.

No lecture or slideshow presentation will ever provide this.

This article was originally published by Loris Occhipinti on Hackernoon.