Sonification of datasets like graphs and using unique perspectives with virtual reality (VR) for an orchestra are all innovative music trends inviting us to new understandings of science and art like only music can.

The 2017 hurricane season saw many graphs with complex data that were difficult to fully comprehend for the serious threats posed. A graph as a picture may be worth a thousand words but when made audible is worth millions of musical notes. Two professors from Pennsylvania State University (Penn State) in the US are making the science of datasets from the weather and the universe more approachable, understandable, and educational with sonification into music.

Professor of Music Technology and Theatre at Penn State University, Mark Ballora Ph.D.

Mark Ballora Ph.D., Professor of Music Technology and Theatre, Pennsylvania State University and Jenni Evans Ph.D., Professor of Meteorology, Pennsylvania State University are turning environmental data into music by associating each value of a dataset with a sound from a synthesized instrument and then making the dynamics of the data have matching dynamics of sounds: speed, rhythm, pitch, volume, etc. just like a music score for a song.

Director at Institute for CyberScience and

Professor of Meteorology at Penn State University, Jenni L. Evans Ph.D.

They work in the Arts & Design Research Incubator at Penn State’s College of Arts and Architecture and use the music synthesis program SuperCollider. While the instrument sounds are chosen to compliment each other, there is nothing added or subtracted from the data for the sake of making the effect more musical. The data speaks, or rather plays, for itself.

This video is an example of data from a graph on one factor, water temperatures changing, which has been sonified:

Next, in transposing Hurricane Sandy’s multiple types of data into music, these professors said “air pressure is conveyed by a swirling, windy sound reflecting pressure changes. More intense hurricanes have lower values of air pressure at sea level. The winds near the ground are also stronger in intense storms. As pressure lowers, the speed of the swirling in our sonic recordings increases, the volume increases, and the windy sound becomes brighter.”

Traditional visual representation of data into graphs has its limitations for both people with visual disabilities such as sight loss and color-blindness as well as some cognitive disabilities, making sound-based representation more accessible. Additionally, sound is something that we commonly train ourselves with to find patterns, fluctuation, and variance: recognizing music heard before, recognizing familiar voices, memorizing information in songs like the ABCs, understanding sounds from multiple sources at once, and learning stories or culturally significant values in songs. With our sound training, we are more adept at hearing changes in data, no matter how slight, much more so that visually. Lastly, audio information is processed quicker and more viscerally than visual information.

Dr. Ballora explained, “Even for experts in meteorology, it can be easier to get a sense of interrelated storm dynamics by hearing them as simultaneous musical parts than by relying on graphics alone. For example, while a storm’s shape is typically tied to air pressure, there are times when storms change shape without changing in air pressure. While this difference can be difficult to see in a visual graph, it’s easily heard in the sonified data.”

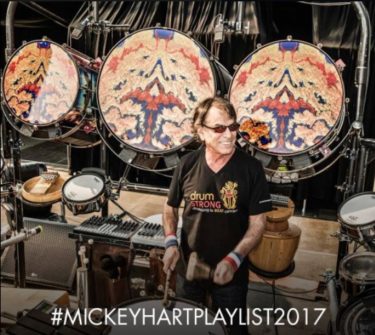

Mickey Hart

Dr. Ballora’s sonifications have moved beyond the weather to take into account datasets of astronomical and physiological properties of the universe, which Mickey Hart (famed drummer/percussionist of Grateful Dead) has integrated into performances of the Mickey Hart Band and their albums Mysterium Tremendum and Superorganism.

George Fitzgerald Smoot III Ph.D. (US astrophysicist, cosmologist, Nobel laureate, and professor at UC Berkeley Physics) collaborated on the film Rhythms of the Universe, which debuted in 2013 as a 22-minute short, multi-sensory film experience.

Professor at UC Berkeley Physics, George Fitzgerald Smoot III Ph.D.

The two driving forces in this poetic film were to make the topic attractive to viewers and to keep sonification intrinsically related to the data sets with complete integrity.

Music has become more approachable for the classical music genre too, with the use of VR for a unique perspective. For example, in speaking with Blandine Berthelot, the musicologist at Insula orchestra, she has the demanding task of making more connections between classical music and technology, in the hope that more people will be drawn to the orchestra and classical music.

Conductor at Insular orchestra (France), Laurence Equilbey

Her orchestra’s conductor, Laurence Equilbey, is an open-minded conductor, eager to approve Blandine’s projects.

Mozart 360 at Saint-Omer Cathedral in France

One project, Mozart 360, was the first to take the VR user on a 3D journey of visual and audio changes through an orchestra, on the stage with the orchestra, not from the audience’s perspective. The user’s 3D audio shifts and rebalances as the user “sits” in different instrument sections, thus the sound in the violin’s section is what the violinists actually hear, not what you’d hear way out in the audience. The theme was to “connect classical music with people from whom Mozart is remote”, according to Blandine.

During the journey, the user is gestured to by the conductor, which the user sees from the front (unlike an audience member who only sees her back) and can hear the immediate responses from the entire section or from a specific player. As most of us will never know the real experience of being a virtuoso, playing in a famous orchestra, and demonstrating our musical finesse in the Saint-Omer Cathedral, as one viewer explained, she was “right at the heart of the concert; you’re carried away by the music.” Blandine added that Mozart 360 was “an experimental journey through the raw material of sound.”

Blandine shared that the “median age of the classical music audience in France is 61 (from a 2015 survey by sociologist Stéphane Dorin)”, and classical music must be made more approachable to those of all ages and with new access points for people with interests not commonly associated with classical music, such as VR and music tech. On the orchestra’s Facebook page, they try to share a number of new projects from young people being introduced to the performers and backstage preparations in Mozart Matrix and 24 hours with Bruno to a FlashMob and a mock trial surrounding their conductor, all meant to take away the serious veil that often shrouds classical music and expose the engaging personalities and humor found within.

There is a global welcome to music experiments like Blandine and the Insula orchestra are creating, as music is the universal language, with no language barrier. There is even a universal language of people in the arts, depending more upon their art form and the global superstition that saying “good luck” is the catalyst for bad luck.

For example, the world over, all dancers say “merde” (French for “shit”) before moving onto the stage. Similarly, singers say “toi toi toi” before going live, which sounds like “toy” and is taken from the German word for devil, Teufel. The response to the toi trio is “I’ll take that.” Specifically, opera singers may like to use “In bocca al lupo” (Into the wolf’s mouth), with “Crepi il lupo” (Let him perish!) as the customary response.

In the live production world of theatre, actors use the famous “break a leg.” Whereas “break a string” made be said to those musicians of stringed instruments, “break a leg” is really okay to say to anyone going live on stage. Lastly, “Bump a nose!” is customary in the world of circus performers.

The full Mozart 360 experience is available online and through an app from Arte360. The Mozart 360 project was directed by Laurent Colin, produced by Chloé Jarry and ARTE 360 ° VR INSULA, with the production company Camera lucida productions.